Calegari

Calegari

Antonio Calegari (1757 - 1828)

|

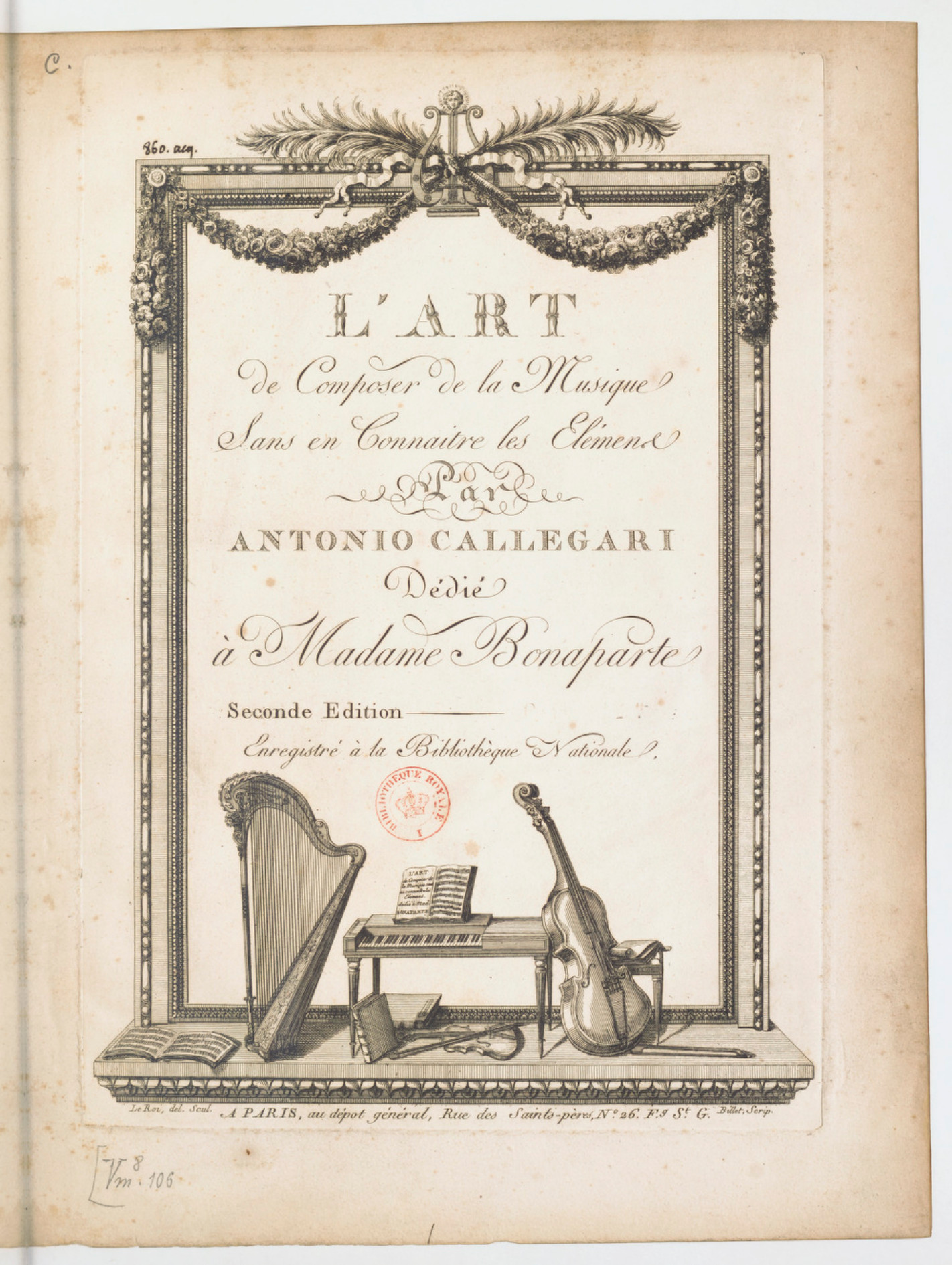

| The original cover for the publication "L 'Art de composer de la musique sans en connaitre les elements" (click to enlarge). |

Composer Antonio Calegari Sr. was born in Padua on February 17, 1757. After a short stay in Venice in 1800, he returned to Padua where in 1801 he was the first organist of the Basilica del Santo, and in 1814 he became musical director. Calegari wrote numerous stage works and spiritual compositions. He also proved himself as a theoretician with "Trattato del sistema armonico", posthumously published by his student M. Balbi in 1829, one year after his death. In 1791 he became a member of the Academia Filarmonica in Bologna.

In 1801, a musical dice game by Calegari, titled "Gioco Pitagorico Musicale, col quale potrà ognuro, anco senza sapere di musica, formarsi una serie quasi infinita di picciole ariette, e duettini, per il tutto coll'accompagnamento del piano forte, o arpa, o altri strumenti" (Game of Pythagorean Music, with which anyone, even without knowing music, can compose an almost endless series of small songs and little duets, all with the accompaniment of the pianoforte, or harp, and other instruments ), was published by Sebastian Valle in Venice. In fact, the publication contains not one, but five different dice games: aria for solo voice with piano (selected for this project) and four others containing duets with piano, the last one as a three-part rondo with ritournelle. The second duets dice game was also selected.

His musical game received such a large popularity that just a year later, a second edition was published by Boudin in Paris. This time it had the title "L 'Art de composer de la musique sans en connaitre les elements" and it was dedicated to Josephine Bonaparte. This entertaining gimmick did not find unanimous approval. There were, for example, critical voices with great influence that achieved that Calegari's membership of the earlier mentioned Academia was withdrawn because of the publication of the dice game. Through this, it became clear how the dice music was often misunderstood. It must simply be taken for what it wants to be, namely as a joke, a game, an innocent entertainment on long winter evenings. Dice music does not want to be a noble art with a highly philosophical background. Whoever approaches the phenomenon in a serious way bypasses its very essence, by which a reaction as described earlier is easily understandable.

The main difference of the "Gioco" compared to other musical dice games is that it is not designed purely instrumental, but written for voice with accompaniment of the piano (the harp or other instruments). This was at that time an entirely uncommon constitution. The focus was no longer solely on a possible combination of individual bars, but also a meaningful distribution of text had be respected. Formally, Calegari is disregarding the strict symmetry of the dice games of the old masters by making the second part of the aria two bars longer than the first. The text will not be 'diced', but can be relatively freely written poetry. Each verse must consist of eight syllables, corresponding to two musical bars. The last verse is repeated.

In older games, melody (e.g. violin) and right hand of the piano part, as a rule, are very closely linked (colla parte), while in this case the piano in relation to the voice is relatively independent. The bass is quite independent and results in all conceivable bar combinations in a different part. So it is not in all cases the same continuous voice like with Mozart. Neither is it involved in the motivic pattern like with Kirnberger. The bass takes on a whole new dimension: it is no longer only the foundation, but neither it is a contrapuntually equal partner to the upper voice. It rather seems that the bass is adjusted to the upper voice, and no longer as in the Baroque period, where the upper voice is following the bass. Harmonically, there are some notable dissonances that are unthinkable in older games in such a way. Rhythmically, Calegari aims at variation, but not at the expense of a distinctive flowing style. The vocal line, especially in the voice is relatively simple, small intervals are predominant. The transitions are very correct; dissonances are usually resolved correctly.

Summarizing, Antonio Calegari's "Gioco Pitagorico Musicale", as many musical dice games, is principally based, on Kirnberger's "Der allezeit fertige Menuetten- und Polonaisencomponist". However, on many points, it deviates from its model and goes its own way. The aria part of Calegari’s "Gioco", together with Wi(e)deburg's "Chartenspiel", is the most interesting and most successful of all described dice games.

Aria implementation note

In the Aria we only used the measures written for the dice game itself. Calegari also wrote measures for alternatives ending for some of the dice throws. These alternative endings should produce greater musicality. We have chosen to implement only the basic game.

Sources- Haupenthal, Gerhard (1994), Geschichte der Würfelmusik in Beispiele, 2 Volumes, University of Saarbrücken.